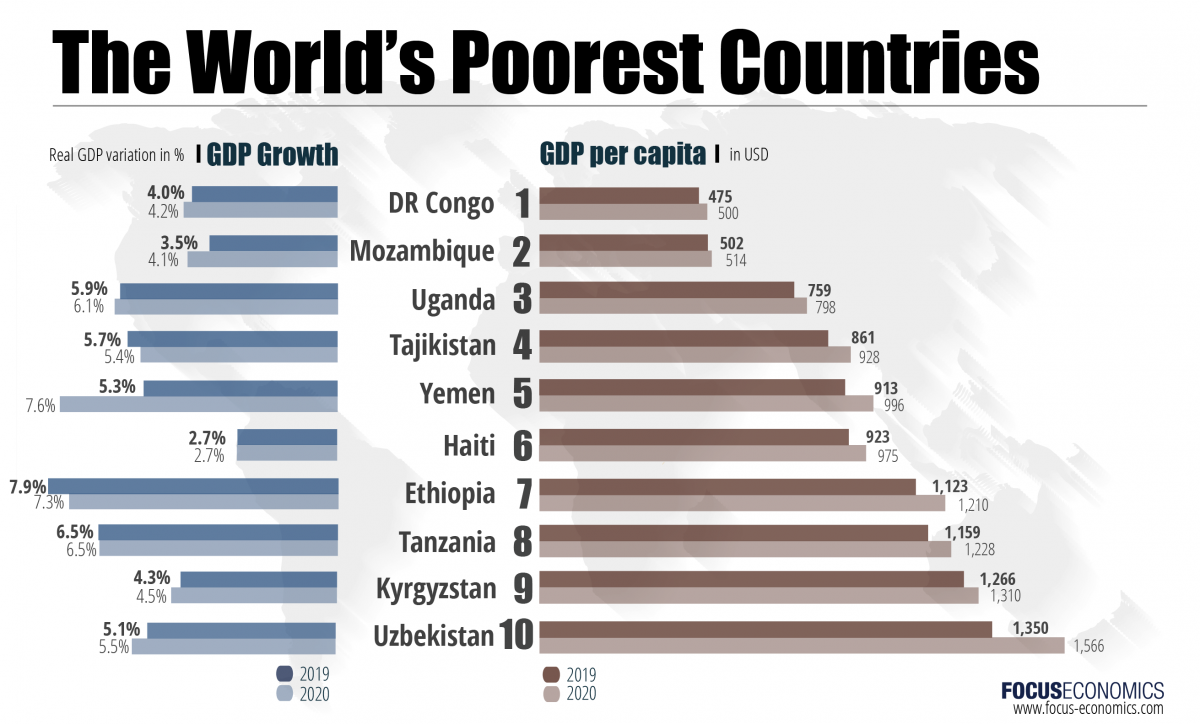

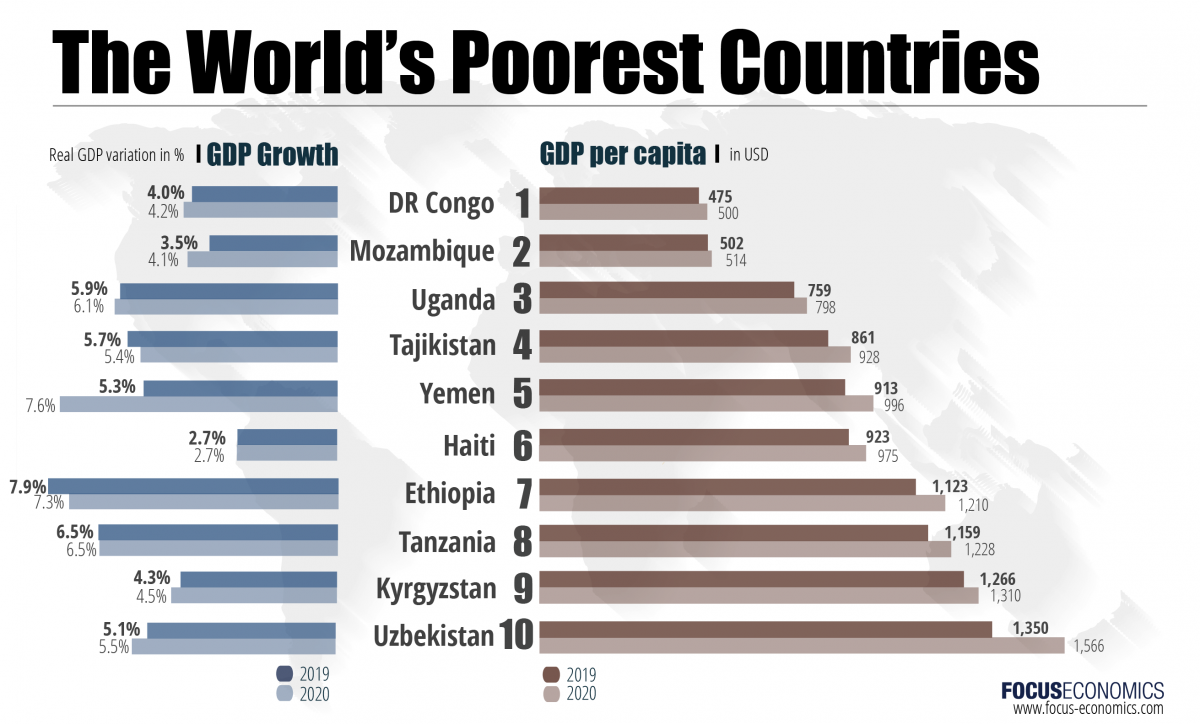

GDP per capita is often considered an indicator of the standard of living of a given country, as it reflects the average wealth of each person residing in a country. It is therefore the standard method used to compare how poor or wealthy countries are in relation to each other. With 2018 coming to a close, we decided to take a look at our forecasts for GDP per capita from 2019 to 2023 for the 127 countries we cover to get an idea of what countries are the poorest currently and which will be making a leap toward becoming wealthier in the coming years. The projections used in this study are Consensus Forecasts based on the individual forecasts of over 1000 world renowned investment banks, economic think tanks and professional economic forecasting firms.

focuseconomics_poorest_countries_nov_2018-01.png

ty

ty

Click image to view larger version – See the full list below

As one might imagine those closest to the top of the list are mostly emerging markets and least developed countries of which the majority are from Sub-Saharan Africa. Similar to our ranking for the most miserable economies, this is one of those lists where the “winners” aren’t really winners; being as far from the top of the list as possible is a good thing.

Many of the poorest nations in the world are places where issues such as authoritarian regimes, political turmoil, weak financial institutions, inadequate infrastructure and corruption deter foreign investment despite the fact that many of them are immensely rich in natural resources and have a young, growing population. In our list of the top 10, five are landlocked, which means they have no direct access to maritime trade and another one is in the midst of a civil war, which helps to explain why some of them are currently not in the best of shape.

Despite how grim that may sound, these countries stand to benefit the most in the coming years as emerging markets will become vitally important to the global economy. Although per capita GDP will still be the highest in the developed world by 2023, the fastest growth in GDP per capita will indeed come from many of the world’s poorest economies currently. According to our forecasts, the highest per capita growth from 2017–2023 will be in Mongolia with an 89% increase in that time span, followed by Myanmar, Egypt, Serbia and Bangladesh with 83%, 80%, 79%, and 67% growth in per capita GDP, respectively.

With that said, let’s have a look at the poorest countries in the world according to the FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast for 2019 nominal GDP per capita.

1. Democratic Republic of Congo

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 439

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 475

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 551

Although the DRC has abundant natural resources, unfortunately with a projected 2019 GDP per capita of USD 475, the country is in the unenviably position of being the poorest country in the world. There has been severe political unrest in recent years, as calls for President Joseph Kabila, who took power after the assassination of his father in 2001, reached a fever pitch in 2018. Kabila was reelected in 2011 in a controversial election and had since postponed elections several times. Finally in August, Kabila declared that he would not seek re-election and named a successor candidate. The next presidential election has been slated for 23 December and opposition parties selected well-known businessman and veteran legislator, Martin Fayulu, as the unity candidate on 11 November following lengthy talks in Geneva. Fayulu has been one of the fiercest critics of President Joseph Kabila’s tight grip on power. While strong activity in the extractive sectors has supported firm growth, the long-delayed elections have led to a tense business environment and a slowdown in overall activity. Moreover, Katanga Mining (a subsidiary of Glencore) announced a temporary halt to cobalt production at its Kamoto mine, after high levels of uranium were discovered.

Strong demand for key export commodities, including copper and cobalt, is expected to drive growth next year. Moreover, a sharp decline in inflation should buoy domestic demand. Political risks, however, darken the outlook. FocusEconomics analysts have thus far priced-in a peaceful transition of power—which would mark the first since independence in 1960—projecting growth of 3.7% in 2019 and 4.3% in 2020.

2. Mozambique

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 429

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 502

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 648

The second poorest country in the world is Mozambique with a forecasted GDP per capita of USD 502 for 2019. The former Portuguese colony has high hopes of transforming its economy based on prospects of abundant natural gas fields discovered in 2011. The country recently took an important step toward said transformation with the approval of a USD 20 billion Anadarko liquified natural gas plant in early-2018, which envisages exploiting the country’s vast deposits of natural gas.

Economic growth is expected to accelerate this year on the back of higher prices for natural gas. FocusEconomics panelists see growth of 3.5% in 2018 and 4.1% in 2019.

3. Uganda

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 726

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 759

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 959

Uganda finds itself in third place on the list with a 2019 projected GDP per capita of USD 759. Although this represents a large leap from the level of the first two on the list, Uganda is a bit of a strange case. Following the 1986 armed conflict, the ruling political party National Resistance Movement (NRM), enacted a series of structural reforms and investments that led to a period of significant economic growth and poverty reduction all the way up to 2010. In the last five years or so, economic growth has slowed and consequently so has the pace of poverty reduction. There are a variety of factors that have brought on the slowdown, however, it has been attributed mostly to adverse weather, private sector credit constraints, the poor execution of public sector projects and unrest in their neighbor South Sudan, which has flooded the country with refugees fleeing the country and subdued exports. According to the World Bank, if Foreign Direct Investment accelerates, the banking system stabilizes, and budgeted, capital spending is executed without delays, the economy may start to pick up once again, helping to reduce poverty.

Luckily for Uganda, it appears the FDI is indeed improving according to the latest confiremd data, expanding by double digits in 2017, which bodes well for the economy and poverty reduction in the near future. The downside risk to the outlook is the weakness in the financial system, particularly the low level of credit in the private sector and the high cost of small loans. FocusEconomics panelists see growth of 5.9% in 2019 and 6.1% in 2020.

4. Tajikistan

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 777

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 861

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1159

Tajikistan is number four on the list of poorest countries with a projected 2019 GDP per capita of USD 861. Tajikistan gained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union, however, a civil war broke out shortly after, which lasted five years until 1997. Since then, political stability and foreign aid have allowed the country’s economy to grow, reducing poverty rather remarkably. According the World Bank, poverty fell from over 83% to 47% between 2000 and 2009 and fell further from 37% to 30% between 2012 and 2016. Since then, poverty reduction, has regrettably stagnated, however, it is projected to fall from 30% to 25% by 2019 as growth picks up.

The economy, which is highly reliant on remittances, is expected to grow strongly in again 2019. Improving labor market dynamics, and a continued robust inflow of remittances supported by Russia’s ongoing economic recovery, should buoy private consumption. Headwinds to the growth outlook include a less supportive external environment owing to tighter global financial conditions and the escalating tit-for-tat trade war. The economy is seen growing 5.7% in 2019 and 5.4% in 2020.

5. Yemen

2016 GDP per Capita: USD 762

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 913

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1079

Yemen is in the midst of massive civil war that has caused a catastrophic humanitarian crisis, which goes a long way to explaining the country’s place on this list of the poorest countries in the world. Yemen is forecast to have a GDP per capita of USD 913 in 2019. Basic services across the country are on the verge of collapse, as half of the population is currently living in areas directly affected by the conflict and millions of Yemenis have been forcibly displaced.

Yemen is also facing the worst famine in a century, according to the United Nations, with 14 million people at risk of starvation. After peace talks failed to get off the ground in September, fighting only intensified. In recent weeks, the unofficial exchange rate has come under pressure despite a USD 200 million cash injection from Saudi Arabia into Yemen’s Central Bank in October, while Yeminis around the country have protested for better living conditions.

Following three-and-a-half years of civil war, the economy is expected to return to growth for the first time in six years in 2019; albeit thanks in part to a miserably-low base effect. FocusEconomics expects the economy to expand 5.3% in 2019 and 7.6% in 2020.

6. Haiti

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 776

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 923

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 993

Haiti is number six on the list with an expected GDP per capita of USD 923. Haiti is extremely vulnerable to extreme weather and natural disasters with 90% of the country’s population at risk according to the World Bank. These natural disasters batter the country in more ways than one, including the economy. The 2010 earthquake for example did damage equivalent to 32% of the country’s GDP.

Although there is some positive sentiment over Haiti’s political situation, as new president Jovenel Moïse took office in February of last year and the new parliament and cabinet were ratified later in the year, which should allow the country to accelerate reforms and move public programs forward to create a more sustainable development for all Haitians, the country remains the poorest in the Americas. More than 6 million out of 10.4 million Haitians live under the national poverty line of USD 2.41 per day and over 2.5 million live under the national extreme poverty line of USD 1.23 per day according to the latest household survey (ECVMAS 2012). As far as income equality goes, it is also one of the most unequal, with a Gini coefficient of 0.59 as of 2012.

While the economy started 2017 on a solid footing, economic activity has decelerated since, mostly due to the negative impact of Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Furthermore, the U.S. administration’s decision to scrap Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Haitians as of July 2019 threatens all-important remittance inflows, which account for around 34% of the country’s GDP. As a result of this decision, around 60,000 Haitians currently living in the U.S. could be forced to return to Haiti.

Growth should accelerate in 2019, though the country’s prospects remain hampered by rampant corruption and political instability. Growth is projected to come in at 2.7% in 2019 and 2.7% again in 2020.

7. Ethiopia

2016 GDP per Capita: USD 884

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1122

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1508

Back to Africa now with number seven on the list, Ethiopia is located in the Horn of Africa, which gives it a great strategic jumping off point, as it is close to the Middle East and its markets. Although it is technically landlocked, it’s tiny bordering neighbor, Djibouti acts as its main port. Ethiopia has grown rapidly since the turn of the century, and is currently the fastest growing country in Africa, although extremely poor as evidenced by its projected 2019 GDP per capita of just USD 1122.

Along with Ethiopia’s rapid economic growth came significant reductions in poverty with over 55% of Ethiopians living in extreme poverty in 2000 dropping to 33.5% in 2011, according to the World Bank. To sustain its economic growth and poverty reduction, good governance is needed, however, significant public unrest has taken hold in Ethiopia of late over the country’s authoritarian regime.

In a bid to cool mass unrest and open the way for economic reforms, Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn submitted his resignation on 15 February. In October, parliament approved Sahle-Work Zewde to become the country’s first female president—a sign of political openness from Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. Growth should remain robust in FY 2018, although is likely to slow somewhat as the government restrains public investment growth to limit imports. That said, an improving business environment following market-friendly economic reforms could propel stronger activity in the private sector. FocusEconomics sees the economy growing 8.2% in FY 2018 and 7.6% in FY 2019.

8. Tanzania

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 1037

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1159

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1502

Number eight on the list of poorest economies is Tanzania with an expected USD 1159 GDP per capita for 2019. Tanzania’s economy has been very consistent over the last decade averaging between 6 and 7% growth every year. According to the World Bank, the poverty rate has also steadily declined, however, the absolute number of people living in poverty has not due to the high growth rate of its population over that time.

Economic prospects for Tanzania depend on infrastructure investment, improving the business environment, increasing agricultural productivity, amongst others and growth prospects for next year remain strong. The economy should continue to expand solidly, supported by sustained infrastructure spending and growth within the services sector on the back of growing tourist inflows. FocusEconomics expects GDP to expand 6.5% in 2019, which is unchanged from last month’s forecast, and 6.4% in 2020.

9. Kyrgyzstan

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 1203

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1266

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1488

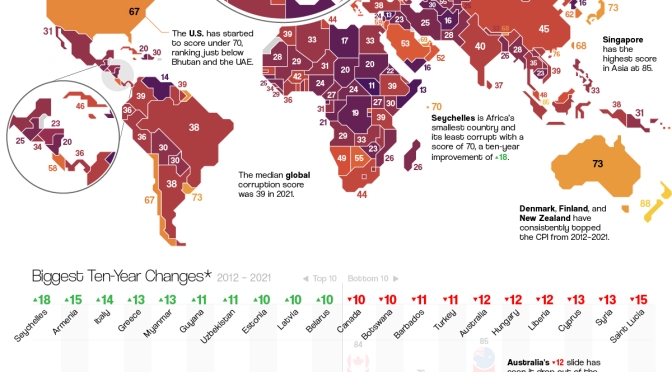

Kyrgyzstan is ninth on the list with an expected 2019 GDP per capita of USD 1266. A landlocked, largely mountainous country with just over 6 million inhabitants, the Kyrgyz Republic recently adopted a parliamentary system in 2011. Having experienced considerable political and social instability with weak governance and high corruption since gaining independence in 1991, the country’s current democracy is a far cry from those days. Nonetheless corruption is still pervasive in the public sector, which constrain the country’s economic growth potential.

The Kyrgyz economy is also vulnerable to external shocks due to its overreliance on its massive gold mine, Kumtor, which accounts for about 10% of GDP, as well as remittances, which amount to about 30% of GDP.

Growing gold production in September at the all-important Kumtor mine powered the rebound in economic activity recorded in the January–September period, when GDP increased slightly in annual terms, from the small contraction recorded in January–August. That said, cumulative mining output in January–September was still much lower than in the same period last year, which translated into falling exports. On the other hand, during the same time span, sustained wage increases and rising remittances led to a solid expansion in retail sales while both capital investment and construction increased strongly.

GDP growth is set to accelerate next year, as production at the Kumtor gold mine increases, driving output growth in the industrial sector. Solid consumer spending, fueled by healthy wage growth and higher remittances from Russia, will also underpin the expansion. A possible cooling in economic activity in Russia due to U.S. sanctions, however, cloud the outlook. FocusEconomics projects GDP growth of 4.3% in 2019 and 4.5% in 2020.

10. Uzbekistan

2017 GDP per Capita: USD 1514

2019 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 1350

2023 GDP per Capita (projected): USD 2351

Uzbekistan is last on the list of poorest countries according to 2019 GDP per capita, which is forecast to come in at USD 1350. The country’s economic growth was fast between 2004 and 2016, lifting significant portions of the country out of poverty. A country rich in commodities, Uzbekistan was aided by high commodities prices and increased exports of gas, gold and copper, which generated state revenues that financed large increases in investment and wages that bolstered private consumption.

Unfortunately, in the period between 2013 and 2016, commodities prices came crashing down along with the weak performance of Russia and China, key trade partners, adversely affected the economy. Despite the external environment weakening, the government’s countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies allowed growth to slow only slightly, however, poverty reduction has largely stagnated.

In February of 2017, the government began implementing its Strategy of Actions for the Development of Uzbekistan for 2017-2021, which among other things included measures to liberalize its economy. One measure was implemented in September of 2017, which linked the official exchange rate with the curb market rate and established a framework to allow it to flow.

Unfortunately, the economy moderated sharply in 2017 to 5.3% from 2016’s 7.8%, the slowest print since 2003. The moderation partly reflected the impact of the currency devaluation, which had caused inflation to spike and real disposable income to drop. It also underscored the short-lived impact that many market-friendly reforms pushed ahead by the government to attract foreign investment are having on the economy.

The economy grew 5.2% annually in the January–September 2018 period, driven by a strong services sector and solid industrial output. Industrial activity was propped up by soaring mining and quarrying production, largely thanks to a booming natural gas sector. In addition, construction activity expanded robustly in the same period, supported by buoyant demand for real estate amid easing inflationary pressures. On 19 October, authorities began preparatory work on the country’s first nuclear plant, estimated to cost USD 11 billion and largely financed by Russia, in a bid to further strengthen Uzbekistan’s energy sector. The government has also signed multibillion-dollar economic and investment deals with Russia and the U.S. as the country continues its pro-liberal economic policy push.

In 2019, growth should remain solid on the back of sustained government spending, healthy capital investment and a growing inflow of remittances from Russia. FocusEconomics expects the economy to expand 5.1% in 2019, down 0.4 percentage points from last month’s forecast, and 5.5% in 2020.

You can see the entire list below of our projections for GDP per capita for 2018 below. If you’d like to get more historical data, Consensus Forecasts, charts, graphs and written analysis from our team of economists, download a free sample report by clicking on the button below the table.

GDP Per Capita 2019-2023

2019 Rank Country GDP per Capita 2019 (projected) GDP per Capita 2017 (actual) 2017 Rank GDP per Capita 2023 (projected) 2023 Rank

1 DRC 475.3217 438.5256 2 551.3249 1

2 Mozambique 501.9192 429.3636 1 647.641 2

3 Uganda 759.0817 725.9486 3 959.4522 3

4 Tajikistan 861.2937 777.0268 5 1158.827 6

5 Yemen 912.5141 – N/A 1079.137 5

6 Haiti 922.7217 775.8355 4 992.7961 4

7 Ethiopia 1122.567 – N/A 1508.321 9

8 Tanzania 1159.105 1037.079 6 1502.31 8

9 Kyrgyzstan 1266.064 1203.071 7 1487.614 7

10 Uzbekistan 1350.473 1513.999 10 2350.817 14

11 Zambia 1479.781 1566.378 13 1858.185 10

12 Pakistan 1495.477 1546.844 12 1869.015 11

13 Myanmar 1533.067 1278.07 8 2337.462 13

14 Cambodia 1627.842 1383.751 9 2194.383 12

15 Bangladesh 1774.44 1521.366 11 2547.109 18

16 CDI 1899.69 1618.134 14 2526.718 17

17 Kenya 1960.507 1691.498 15 2357.122 15

18 Nicaragua 2151.084 2220.543 19 2388.447 16

19 India 2171.269 1979.313 16 – N/A

20 Nigeria 2318.455 1994.661 17 2988.712 19

21 Ghana 2434.003 2061.11 18 3278.356 21

22 Vietnam 2749.925 2354.901 20 3750.412 22

23 Laos 2898.278 2522.904 22 3925.37 24

24 Honduras 2909.249 2773.835 25 3202.053 20

25 Egypt 2924.286 2471.783 21 4439.591 30

26 Ukraine 3033.515 2685.161 23 4237.628 28

27 Angola 3041.152 4388.521 40 4274.436 29

28 Philippines 3306.841 2989.068 26 4560.859 31

29 Moldova 3347.066 2761.133 24 3922.999 23

30 Tunisia 3502.351 3479.192 29 4155.141 26

31 Morocco 3513.398 3159.52 27 4120.344 25

32 Bolivia 3727.982 3388.005 28 4228.401 27

33 Venezuela 3887.217 – N/A – N/A

34 Indonesia 4042.662 3875.781 32 5480.01 37

35 El Salvador 4172.125 3894.715 33 4782.359 32

36 SriLanka 4264.391 4071.251 36 5565.878 38

37 Algeria 4281.844 4036.28 35 5369.218 34

38 Georgia 4322.538 4265.342 39 5765.187 42

39 Armenia 4462.305 3862.116 31 5681.698 41

40 Azerbaijan 4505.525 4148.86 37 5449.05 36

41 Jordan 4554.322 4195.882 38 5436.38 35

42 Kosovo 4669.263 4026.13 34 6298.403 43

43 Mongolia 4694.103 3639.977 30 6886.963 45

44 Guatemala 4769.698 4466.347 41 5613.315 39

45 Belize 4850.095 4825.427 43 5025.607 33

46 Iraq 5081.196 4920.48 44 5672.477 40

47 Jamaica 5455.045 5198.3 45 6603.454 44

48 Albania 5532.769 4644.693 42 7033.495 47

49 Iran 5645.365 5634.898 49 7852.415 51

50 Paraguay 6050.501 5633.191 48 7166.749 48

51 Bosnia 6130.693 5309.657 46 8152.124 53

52 South Africa 6135.719 6281.276 53 7491.503 49

53 Belarus 6169.273 5707.975 50 7616.448 50

54 Ecuador 6210.746 6216.598 52 6919.949 46

55 Macedonia 6270.104 5437.174 47 8274.915 55

56 Colombia 6886.258 6377.405 54 8262.014 54

57 Turkmenistan 7203.68 6642.032 56 8020.402 52

58 Peru 7238.793 6748.979 57 9126.309 56

59 Thailand 7572.41 6590.926 55 9494.643 57

60 Serbia 7772.239 5904.748 51 10597.87 60

61 Turkey 8060.201 10541.78 67 11338.95 62

62 Dominican Republic 8245.759 7472.295 58 9693.61 58

63 Botswana 8403.47 7657.871 59 10499.33 59

64 Montenegro 9127.597 7796.785 60 11935.33 64

65 Brazil 9180.12 9895.964 66 11365.09 63

66 Kazakhstan 9346.117 8585.308 62 12053.76 65

67 Argentina 9519.177 14605.17 75 10853.51 61

68 Bulgaria 10008.19 8300 61 13491.55 68

69 China 10148.53 8805.975 63 14442.21 69

70 Mexico 10357.13 9325.097 64 12732.19 66

71 Russia 10640.84 10957.71 69 13289.46 67

72 Malaysia 11354.87 9814.508 65 14714.68 71

73 Costa Rica 12095.84 11626.27 71 14623.26 70

74 Romania 12811.64 10843.51 68 17476.31 73

75 Lebanon 12895.13 11495.45 70 15658.22 72

76 Croatia 15777.19 13814.83 72 20657.06 76

77 Poland 16460.36 13825.27 73 22526.56 81

78 Panama 16568.68 15198.58 77 20195.35 75

79 Chile 16590.26 15117.77 76 20852.7 77

80 Hungary 16660.19 14349.87 74 22278.07 79

81 Uruguay 16907.26 17104.49 81 22389.87 80

82 Oman 17563.99 17102.49 80 18725.36 74

83 Trinidad 17827.89 16146.82 79 21583.47 78

84 Latvia 18610.53 15571.79 78 24869.22 83

85 Lithuania 20364.45 18513.27 83 28160.73 86

86 Greece 20886.22 18638.56 84 25929.76 84

87 Slovakia 20987.53 17639.72 82 27155.12 85

88 Saudi Arabia 22278.18 21095.4 87 24846.53 82

89 Estonia 24123.96 20275.08 85 32358.3 91

90 Portugal 24205.31 21294.77 88 30030.2 88

91 CzechRepublic 24968.04 20492.96 86 33081.46 92

92 Taiwan 25949.99 24382.5 91 31246.56 89

93 Bahrain 26026.56 24237.5 90 29461.96 87

94 Slovenia 27634.46 23494.68 89 35535.75 94

95 Kuwait 28140.95 27129.24 93 31892.92 90

96 Cyprus 29367.9 26081.87 92 36237.79 95

97 Brunei 30294.58 28276.27 95 34070.92 93

98 Malta 31854.31 27326.09 94 41280.48 99

99 Korea 32660.66 29745.07 97 39784.39 96

100 Spain 32672.64 28393.94 96 40600.76 97

101 PuertoRico 32682.34 31229.57 98 40601.42 98

102 Italy 35580.39 32354.72 99 42000.28 100

103 UAE 38756.57 37728.2 100 43211.3 101

104 NewZealand 40429.89 41536.53 104 47487.16 102

105 Japan 41498.26 38175.17 101 47640.65 103

106 Israel 42520.91 41840.48 105 50825.49 104

107 UnitedKingdom 44617.91 39901.32 103 53548.03 105

108 France 44857.76 39889.51 102 53625.24 106

109 Belgium 48540.49 44112.05 106 58460.56 108

110 Canada 48651.49 45080.67 107 55542.25 107

111 HongKong 50164.08 46064.78 109 59466.59 109

112 Germany 50815.83 45275.83 108 62229.67 110

113 Finland 51647.6 46393.24 110 62589.18 111

114 Austria 53807.81 47860.47 111 64806.86 112

115 Netherlands 55453.01 48485.41 112 67414.58 113

116 Sweden 56305.87 52958.5 113 75053.39 118

117 Australia 57171.87 55680.85 114 67846.35 114

118 Singapore 62004.74 57494.65 116 73585.83 115

119 Denmark 62204.32 57359.54 115 74401.73 117

120 Qatar 64788.74 60693.81 118 77778.58 119

121 USA 65132.9 59792.04 117 73856.17 116

122 Iceland 78031.79 73477.01 120 95854.63 120

123 Ireland 79773.38

: Afrika times: Shakir Essa

ty

ty